Judge’s order to take down law firm webpages is unlawful prior restraint

A lawyer’s website contained pages describing past successful litigation against Ford. When that lawyer was in trial on a similar claim against Ford, the trial judge ordered the lawyer to remove the website pages during the pendency of the trial so that jurors were not exposed to it. On appeal, two years after the trial was over and the website was restored, the order was found to be an unlawful prior restraint. On Wednesday, Division Six of the Second District Court of Appeal issued the opinion by Justice Steven Z. Perren in Steiner v. Superior Court (Cal. Ct. App., Oct. 30, 2013, 2D CIV. B235347) 2013 WL 5819545. The decision was significant in three respects:

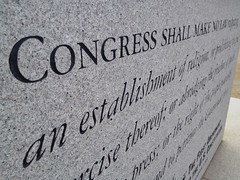

First, it recognized an important limitation on the trial court’s power to curtail an attorney’s free speech rights. The trial court had correctly instructed the jurors not to \”Google\” the attorneys or conduct independent research. Jurors are presumed to follow such admonitions. (Steiner v. Superior Court, at 14; citing NBC Subsidiary (KNBC-TV), Inc. v. Superior Court (1999) 20 Cal.4th 1178, 1221). Absent proof that any juror actually violated the court’s admonition, the trial court had no authority to order the trial attorney to take down web pages as a prophylactic measure.

Second, it was a rare example of a Court of Appeal issuing an order \”after the fact\” when the issue had already become moot. The trial ended in October 2011 and the attorney restored her webpages. The opinion in Steiner did not issue until two years later. Generally, California Courts of Appeal do not issue opinions where the issues are moot and the court has no power to grant any meaningful relief. However, here, the Court of Appeal found that orders such as these raise issues of \”broad public interest\” that are likely in the future to \”evade timely review.\” (Steiner, at 5; citing Nebraska Press Assn. v. Stuart (1976) 427 U.S. 539, 546-547). On this basis, the Court issued the opinion and overruled the objection of mootness.

Third, it is a cautionary tale for appellate counsel not to mislead justices. One of the appellate petitions overstated the breadth of the trial court’s order stating that the entire website of the lawyer had been ordered removed pending trial (as opposed to just two pages that were actually ordered removed). In the Steiner opinion, the Court of Appeal observed regarding appellate counsel Sharon J. Arkin:

It appears she is in violation of Business and Professions Code section 6068, subdivision (d), which states that it is the duty of an attorney “[t]o employ, for the purpose of maintaining the causes confided to him or her those means only as are consistent with truth, and never to seek to mislead the judge or any judicial officer by an artifice or false statement of fact or law.

(Steiner, at 4 fn. 3)

Appellate attorneys who stretch the truth in their briefs risk not only prejudicing their client’s interests but also receiving a sometimes publicized rebuke. Even though this particular attorney was victorious on appeal for her client, the footnote in a published decision is a steep price to pay for zealous advocacy. A Los Angeles legal affairs newspaper was unable to reach Sharon Arkin for comment.